Just in time for the holidays, it’s another edition of Emily’s Library – in which I display the books I’ve given to my now 5-year-old niece, and answer the frequently asked question, “What children’s books would you recommend?” A few of these will be Christmas presents for Emily, who does not (yet?) read my blog. So, if you do see her, don’t spoil the surprise, OK? Thanks.

Kate Beaton, The Princess and the Pony (2015)

The first picture book from the Hark! A Vagrant cartoonist does not disappoint. (I haven’t yet read her second, but Beaton’s King Baby was published this fall.) Princess Pinecone, “the smallest warrior,” would like warrior-suitable gifts for her birthday. Instead, she gets “lots of cozy sweaters.” So, this year, she makes it clear to her parents that she wants a “real warrior’s horse.” But they buy her a little pony, who turns out to be a prolific farter but poor substitute for a warrior horse. Yet, on the day of the contest, Princess Pincone learns that there is more than one way to be strong. My previous sentence makes sounds like a soppy moralistic book. But it isn’t. It’s funny. Warriors getting in touch with their cuddly sides and wearing cuddly sweaters is funny. So is the farting pony. Bonus: though it makes no bones about it, the book subtly integrates a diverse cast of characters: the princess’s mother is a dark-haired brown woman, and her father a yellow-haired white (well, greyish pink) man. The warriors themselves represent a range of body types, races, and genders. In addition to being a fun book, it’s fine example of incidental diversity as well.

The first picture book from the Hark! A Vagrant cartoonist does not disappoint. (I haven’t yet read her second, but Beaton’s King Baby was published this fall.) Princess Pinecone, “the smallest warrior,” would like warrior-suitable gifts for her birthday. Instead, she gets “lots of cozy sweaters.” So, this year, she makes it clear to her parents that she wants a “real warrior’s horse.” But they buy her a little pony, who turns out to be a prolific farter but poor substitute for a warrior horse. Yet, on the day of the contest, Princess Pincone learns that there is more than one way to be strong. My previous sentence makes sounds like a soppy moralistic book. But it isn’t. It’s funny. Warriors getting in touch with their cuddly sides and wearing cuddly sweaters is funny. So is the farting pony. Bonus: though it makes no bones about it, the book subtly integrates a diverse cast of characters: the princess’s mother is a dark-haired brown woman, and her father a yellow-haired white (well, greyish pink) man. The warriors themselves represent a range of body types, races, and genders. In addition to being a fun book, it’s fine example of incidental diversity as well.

Lisa Brown, The Airport Book (2016)

Is it just me, or is incidental diversity (where a character is matter-of-factly non-White) becoming more mainstream? The bi-racial kids (along with their White mother and brown father) are among the many strengths of Lisa Brown‘s The Airport Book, a Richard Scarry-esque journey through airport travel. While we follow the main family of four through the airport, other stories are happening everywhere. Even better: Brown’s attention to detail conveys the sense that they are all real people, and not just there to fill the space. That’s why I compare her pages to Richard Scarry: they’re full of meaningful details, featuring a range of foci for one’s attention. They’re pages to linger over. They capture the simultaneous ongoing activity of these busy spaces. While The Airport Book replicates the divided attention of airports and airplanes, it also offers a singular path forward, via a second-person narration aligned with the older child. All those “yous” invite the child reader to see herself in the book. As a child who travels a lot, Emily will – I predict – recognize herself in these pages.

Is it just me, or is incidental diversity (where a character is matter-of-factly non-White) becoming more mainstream? The bi-racial kids (along with their White mother and brown father) are among the many strengths of Lisa Brown‘s The Airport Book, a Richard Scarry-esque journey through airport travel. While we follow the main family of four through the airport, other stories are happening everywhere. Even better: Brown’s attention to detail conveys the sense that they are all real people, and not just there to fill the space. That’s why I compare her pages to Richard Scarry: they’re full of meaningful details, featuring a range of foci for one’s attention. They’re pages to linger over. They capture the simultaneous ongoing activity of these busy spaces. While The Airport Book replicates the divided attention of airports and airplanes, it also offers a singular path forward, via a second-person narration aligned with the older child. All those “yous” invite the child reader to see herself in the book. As a child who travels a lot, Emily will – I predict – recognize herself in these pages.

Benjamin Chaud, Poupoupidours (2014) [The Bear’s Surprise (2015) in its original French]

If you’re new to my “Emily’s Library” series, I should add here that I’m giving Emily books in French and in German (as well as English) because she’s Swiss and thus growing up tri-lingual. Whether you read Poupoupidors in French, English, or another language, this book concludes the adventures of the Little Bear and his Papa – which began in (if I may use the English-language titles) The Bear’s Song and continued in The Bear’s Sea Escape.

If you’re new to my “Emily’s Library” series, I should add here that I’m giving Emily books in French and in German (as well as English) because she’s Swiss and thus growing up tri-lingual. Whether you read Poupoupidors in French, English, or another language, this book concludes the adventures of the Little Bear and his Papa – which began in (if I may use the English-language titles) The Bear’s Song and continued in The Bear’s Sea Escape.

With die-cut pages offering partial glimpses of what’s to come, Chaud again offers many enticements for curious eyes. In addition to the Where’s Waldo game of finding Little Bear on the busier two-page spreads, there’s the question of what the pages’ windows will reveal when we turn the page. In a twist from the previous books in the series, Papa Bear is not chasing Little Bear: instead, Little Bear (adventuring on his own) finds Papa at the circus.

Tim Egan, Burnt Toast on Davenport Street (1997)

As I wrote back in the early days of this blog,

As I wrote back in the early days of this blog,

Most of his characters are anthropomorphic animals – cows, pigs, dogs, etc. who walk upright, wear clothes, speak in complete sentences. Egan likes to have a little fun blurring the categories between people and animals. The dog protagonists – Arthur and Stella Crandall – of Burnt Toast on Davenport Street (1997) dress well, and live in a beautifully furnished house. They behave like humans. Yet, beneath an illustration of Stella sitting on the couch and Arthur adjusting the TV set’s antenna, Egan writes, “Arthur and Stella were happy dogs. They lived at 623 Davenport Street and had lived there for many years. They spent their days doing what most dogs do. Eating, walking, and sleeping.” Near the end of the book, when the Crandalls are happy, “They both smiled and wagged their tails.” Egan slyly reminds us that, though they dress and act like people, they retain their doggy natures.

Egan is a master. Like James Marshall and Arnold Lobel, his sense of humor arises from mater-of-fact depictions of the mildly absurd. He has a genuine affection for his characters and their predicaments. But, well, you might take a look at my full post on his work. And look for it (Egan’s books, not my post) in your local libraries and bookstores.

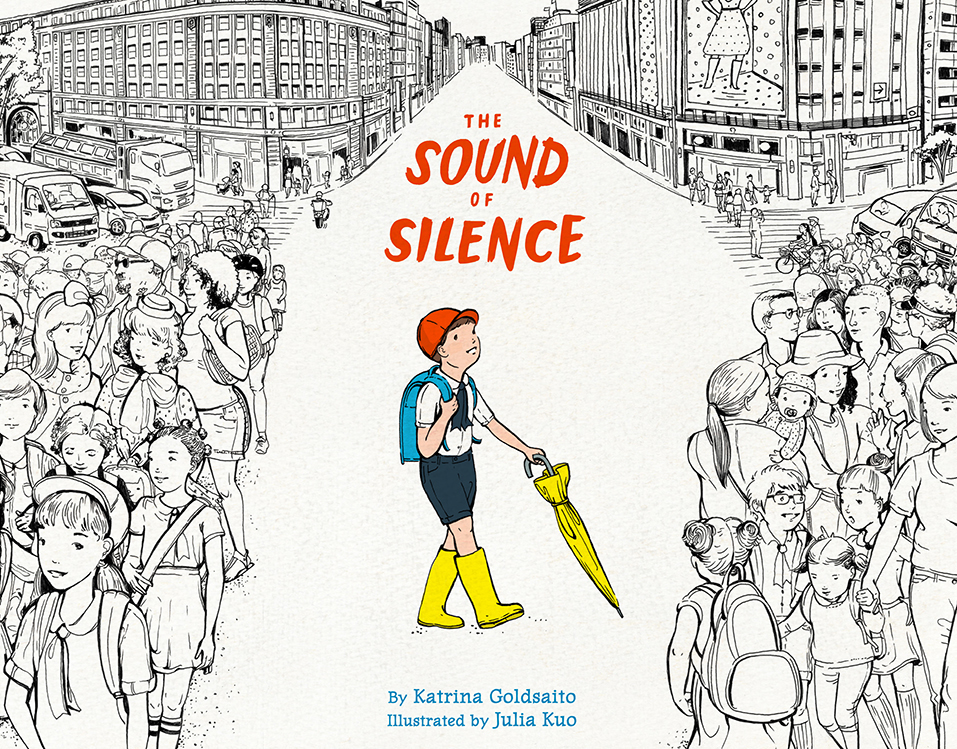

Katrina Goldsaito and Julia Kuo, The Sound of Silence (2016)

With a color palette worthy of Herge, Kuo takes us through Tokyo with Yoshio (the book’s protagonist), searching for ma – the silence between sounds. Along the way, Goldsaito presents the noise of the city, which Kuo depicts, alongside moments of relative quiet – until we (via Yoshio) at last experience that moment of silence. A quest for quietude may seem an unlikely topic for a children’s book (and, yes, I do know Deborah Underwood’s The Quiet Book), but the color, layout, and design of The Sound of Silence immediately hold your attention. In any case, Yoshio’s search is as much about listening as it is about seeking actual silence. It’s about attentiveness to our environment. It’s about noticing.

With a color palette worthy of Herge, Kuo takes us through Tokyo with Yoshio (the book’s protagonist), searching for ma – the silence between sounds. Along the way, Goldsaito presents the noise of the city, which Kuo depicts, alongside moments of relative quiet – until we (via Yoshio) at last experience that moment of silence. A quest for quietude may seem an unlikely topic for a children’s book (and, yes, I do know Deborah Underwood’s The Quiet Book), but the color, layout, and design of The Sound of Silence immediately hold your attention. In any case, Yoshio’s search is as much about listening as it is about seeking actual silence. It’s about attentiveness to our environment. It’s about noticing.

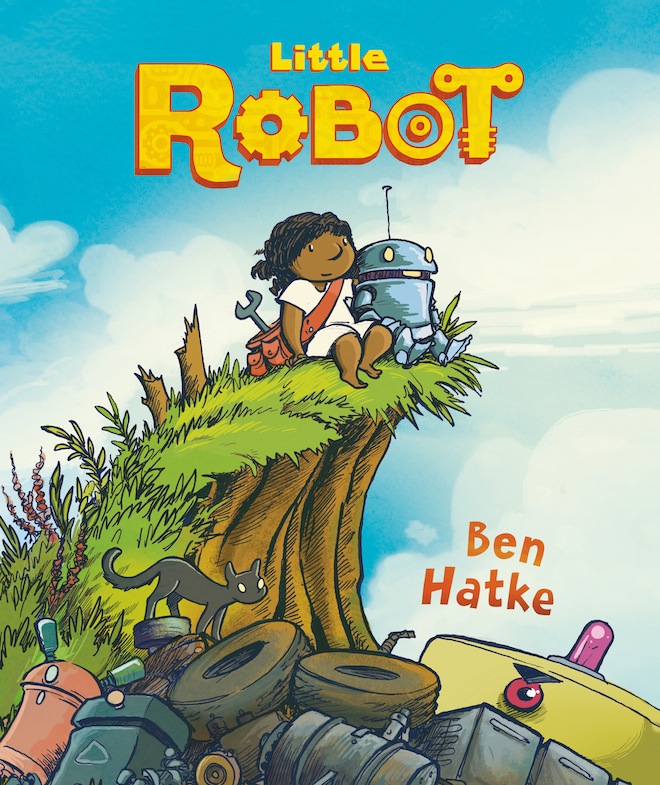

Ben Hatke, Little Robot (2015)

Narrated via the comics medium, Hatke’s gentle tale of a little girl and a robot explores the pair’s developing friendship, as she introduces him to her world, fixing him as needed. But Unit 00012’s creators (an anonymous government agency) want him back, and send a powerful one-eyed robot to capture him. Can our unnamed heroine keep him safe? Its relatively low word-count make this ideal for beginning readers, and its technically savvy brown protagonist brings incidental diversity, as well.

Narrated via the comics medium, Hatke’s gentle tale of a little girl and a robot explores the pair’s developing friendship, as she introduces him to her world, fixing him as needed. But Unit 00012’s creators (an anonymous government agency) want him back, and send a powerful one-eyed robot to capture him. Can our unnamed heroine keep him safe? Its relatively low word-count make this ideal for beginning readers, and its technically savvy brown protagonist brings incidental diversity, as well.

After giving this book to Emily, I heard a fascinating discussion (at a conference) about how and whether Hatke’s portrayal of the little girl participates in stereotypes of strong black women (a criticism that has also been made of the Hushpuppy character in Beasts of the Southern Wild). I continue to find the heroine a compelling one, but mention this criticism to welcome your disagreement – I always read the books I give to Emily before buying them. You should do the same for whomever you’re buying books.

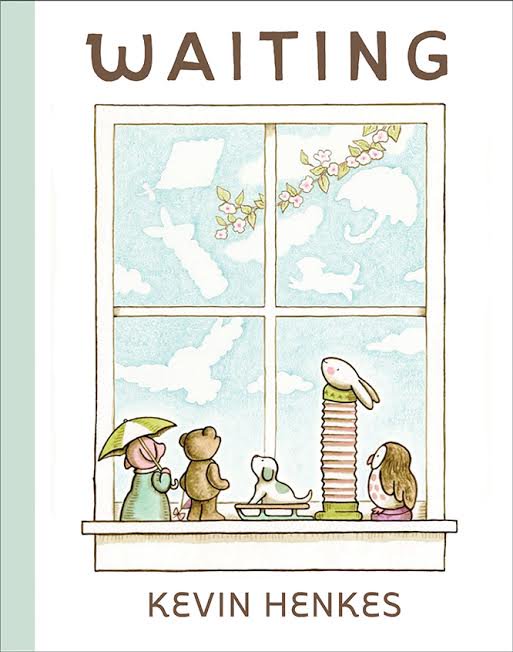

Keven Henkes, Waiting (2015)

On an indoor windowsill, witness five sentient toys: the owl, the pig, the bear, the puppy, and the rabbit. Henkes’ pastel color palette, generous use of negative space, and subtle changes in each toy’s posture or expression swathes the pictures in the aura of a dream, leaving open the question of whether their sentience is real or imagined. This ontological blurriness perfectly captures the reality of childhood imagination – the sense that make-believe is simultaneously real and not real. It also invites engagement with the book’s key question of what the animals await. An early two-page spread seems to answer the question for four of the five, but subsequent pages reveal arrivals for which they were not waiting. Even those events they did await depart from their imagined versions. For instance, “The pig with the umbrella was waiting for the rain.” When it does rain, the observation that “the pig was happy. The umbrella kept her dry” bumps up against a different reality in the artwork. It is raining outside, but the pig is inside and so at no risk of getting wet. They witness the changing seasons, and new arrivals to their windowsill – the last of which affirms their little family. This is a quiet, gentle book, ideal for reflection and dreaming.

On an indoor windowsill, witness five sentient toys: the owl, the pig, the bear, the puppy, and the rabbit. Henkes’ pastel color palette, generous use of negative space, and subtle changes in each toy’s posture or expression swathes the pictures in the aura of a dream, leaving open the question of whether their sentience is real or imagined. This ontological blurriness perfectly captures the reality of childhood imagination – the sense that make-believe is simultaneously real and not real. It also invites engagement with the book’s key question of what the animals await. An early two-page spread seems to answer the question for four of the five, but subsequent pages reveal arrivals for which they were not waiting. Even those events they did await depart from their imagined versions. For instance, “The pig with the umbrella was waiting for the rain.” When it does rain, the observation that “the pig was happy. The umbrella kept her dry” bumps up against a different reality in the artwork. It is raining outside, but the pig is inside and so at no risk of getting wet. They witness the changing seasons, and new arrivals to their windowsill – the last of which affirms their little family. This is a quiet, gentle book, ideal for reflection and dreaming.

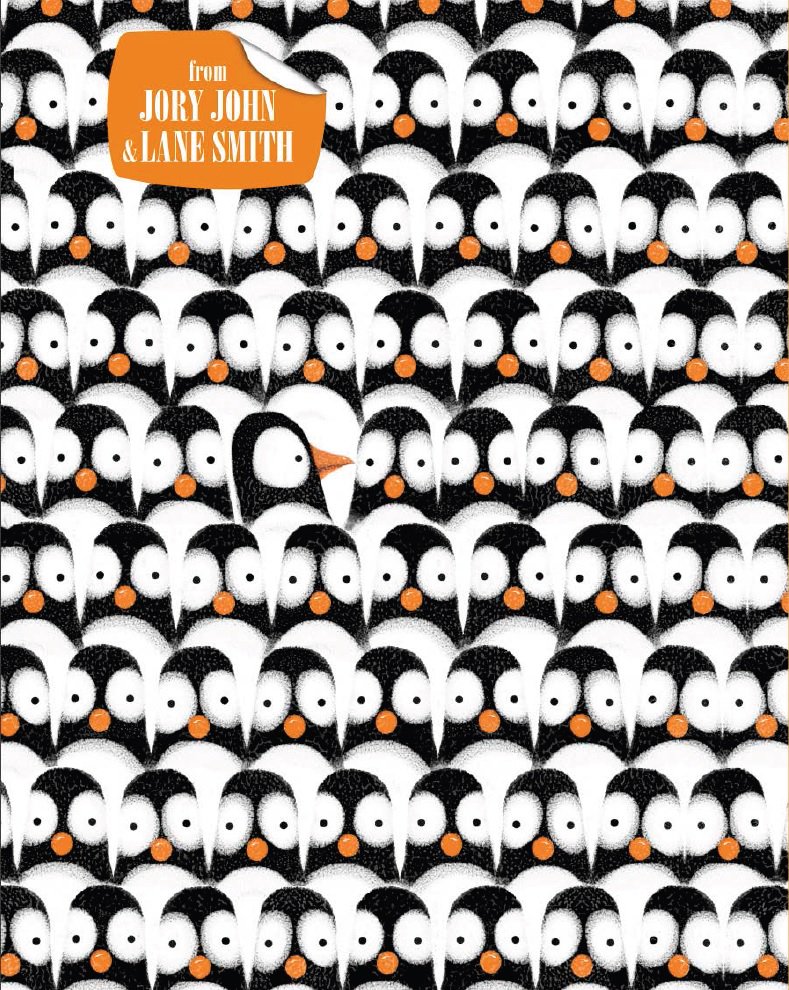

Jory John and Lane Smith, Penguin Problems (2016)

As we arrive at the end of a dark year, I invite you to embrace the gloom of John and Smith’s pessimistic penguin. Penguin Problems is a comic take on a bad mood. And, you know, some people (and penguins) are just not optimistic. Which is fine. In the hands of John and Smith, it’s also funny. Their penguin is cold. He doesn’t like the snow, being hunted by predators, or his flightlessness. Smith gives the penguin an expressive face – big eyes, with eyelids when he’s tired or annoyed. Though the penguin does look like all the other penguins (another complaint of his), readers can also distinguish him from the others. While reading this to Emily, she – unprompted – pointed to him in each crowd scene. Late in the book, a walrus delivers a pep talk, offering a fresh perspective on life. That changes the penguin’s mood for a few pages. But, like I say, some penguins (and people) are pessimists. Frankly, it’s a good time to be a pessimist – as long as you keep your sense of humor about you. Smith and John’s penguin does.

As we arrive at the end of a dark year, I invite you to embrace the gloom of John and Smith’s pessimistic penguin. Penguin Problems is a comic take on a bad mood. And, you know, some people (and penguins) are just not optimistic. Which is fine. In the hands of John and Smith, it’s also funny. Their penguin is cold. He doesn’t like the snow, being hunted by predators, or his flightlessness. Smith gives the penguin an expressive face – big eyes, with eyelids when he’s tired or annoyed. Though the penguin does look like all the other penguins (another complaint of his), readers can also distinguish him from the others. While reading this to Emily, she – unprompted – pointed to him in each crowd scene. Late in the book, a walrus delivers a pep talk, offering a fresh perspective on life. That changes the penguin’s mood for a few pages. But, like I say, some penguins (and people) are pessimists. Frankly, it’s a good time to be a pessimist – as long as you keep your sense of humor about you. Smith and John’s penguin does.

Crockett Johnson, Will Spring Be Early? or Will Spring Be Late? (1959)

This book – which, happily, has recently been reprinted by Harper – reads as a gentle parody of Johnson’s wife Ruth Krauss’s The Happy Day (art by Marc Simont, 1949). In the earlier book, animals emerge from their wintertime hibernation/austerity, jubilant to see a flower growing in the snow. In Johnson’s Will Spring Be Early? or Will Spring by Late?, an artificial flower seems to confirm the Groundhog’s prediction of an early spring – indeed, to confirm that spring is already here! The other animals greet the Groundhog’s news with excitement, delighted that winter is over. Skeptical, the Pig refuses to join the celebrations. Seeing them dancing around the flower, he strolls in, chomps on it, and declares (accurately), “The leaves are paper. The stem is wire. The petals are plastic. And the lot of you will freeze out here.” As the Bear demands an explanation and the Groundhog begins “to creep quietly away,” Johnson leads us to believe that the animals will turn on him. Instead, “They blamed the Pig, of course.” Will Spring Be Early? or Will Spring Be Late wryly transforms a story about welcoming spring (The Happy Day) into a fable satirizing the human tendency to blame the messenger.

This book – which, happily, has recently been reprinted by Harper – reads as a gentle parody of Johnson’s wife Ruth Krauss’s The Happy Day (art by Marc Simont, 1949). In the earlier book, animals emerge from their wintertime hibernation/austerity, jubilant to see a flower growing in the snow. In Johnson’s Will Spring Be Early? or Will Spring by Late?, an artificial flower seems to confirm the Groundhog’s prediction of an early spring – indeed, to confirm that spring is already here! The other animals greet the Groundhog’s news with excitement, delighted that winter is over. Skeptical, the Pig refuses to join the celebrations. Seeing them dancing around the flower, he strolls in, chomps on it, and declares (accurately), “The leaves are paper. The stem is wire. The petals are plastic. And the lot of you will freeze out here.” As the Bear demands an explanation and the Groundhog begins “to creep quietly away,” Johnson leads us to believe that the animals will turn on him. Instead, “They blamed the Pig, of course.” Will Spring Be Early? or Will Spring Be Late wryly transforms a story about welcoming spring (The Happy Day) into a fable satirizing the human tendency to blame the messenger.

Jon Klassen, We Found a Hat (2016)

The third book in Klassen’s “hat” trilogy (Emily already has the first two, I Want My Hat Back [2011] and This Is Not My Hat [2012]), We Found a Hat finds a gentle solution to hat-begotten disagreements. If its peaceful resolution departs from its predecessors, Klassen’s deadpan humor and headwear obsession will please fans of the first two. Dividing the tale into three acts, We Found a Hat tracks two turtles’ discovery (Part One: Finding the Hat), unspoken disagreement on the fairness of single ownership (Part Two: Watching the Sunset), and dream of a shared hat-plentiful future (Part Three: Going to Sleep). It’s a satisfying and unexpectedly sweet conclusion to the series.

The third book in Klassen’s “hat” trilogy (Emily already has the first two, I Want My Hat Back [2011] and This Is Not My Hat [2012]), We Found a Hat finds a gentle solution to hat-begotten disagreements. If its peaceful resolution departs from its predecessors, Klassen’s deadpan humor and headwear obsession will please fans of the first two. Dividing the tale into three acts, We Found a Hat tracks two turtles’ discovery (Part One: Finding the Hat), unspoken disagreement on the fairness of single ownership (Part Two: Watching the Sunset), and dream of a shared hat-plentiful future (Part Three: Going to Sleep). It’s a satisfying and unexpectedly sweet conclusion to the series.

Brothers Grimm & Clementine Sourdais, Rotkäppchen (2014) [Sourdais’ version of Little Red Riding Hood (2015) in German]

Applying a spare color palette (red, black, white) to die-cut pages, Sourdais’ rendering of Little Red Riding Hood can be read two ways. You can unfold the entire book, from first to last page, and see the entire story at once, allowing whatever is behind the page to serve as your artwork’s background. Or you can turn each pair of glossy cardboard pages like a single page in an ordinary book. I confess: I bought this because the cleverness of the art enticed me.

Leo Lionni, Petit-Bleu et Petit-Jaune (1970) [Little Blue and Little Yellow (1959) in French]

Leo Lionni’s first book – invented, initially, to entertain his two grandchildren during a train ride – tells of two colors who become friends. When they hug each other, they become green, and neither set of parents recognizes them. After crying themselves back to their original colors, they revisit the parents who (upon hugging both children) realize that blue hugging yellow creates green. Both families hug each other, and the story ends happily. Given the date of its publication, it’s tempting to read this as advocating friendship between people of different races, and offering a visual metaphor of how such friendships change us for the better. However, the subtlety (and brilliance) of the book is that it doesn’t confine itself to that interpretation. The difference in color could represent any sort of difference, though – to me – the jubilant response to the color transformation suggests how friendships with people of different backgrounds enrich our lives.

Leo Lionni’s first book – invented, initially, to entertain his two grandchildren during a train ride – tells of two colors who become friends. When they hug each other, they become green, and neither set of parents recognizes them. After crying themselves back to their original colors, they revisit the parents who (upon hugging both children) realize that blue hugging yellow creates green. Both families hug each other, and the story ends happily. Given the date of its publication, it’s tempting to read this as advocating friendship between people of different races, and offering a visual metaphor of how such friendships change us for the better. However, the subtlety (and brilliance) of the book is that it doesn’t confine itself to that interpretation. The difference in color could represent any sort of difference, though – to me – the jubilant response to the color transformation suggests how friendships with people of different backgrounds enrich our lives.

Leo Lionni, Fish Is Fish (1970)

In another tale of friendship, a fish and a tadpole reckon with the latter’s transformation into a frog. When the now-grown frog describes all he has seen above the surface of the water, the fish’s imagination conjures up very piscine versions of birds, cows, and people. Lionni’s depictions of these fish-centric creatures are clever and amusing, and introduce a problem: the fish wants to see these sights, too! His attempt to do so leaves him “gasping for air” on the bank. The frog, who happened to be nearby, pushes him back into the pond and saves his life. Are the book’s final words “fish is fish” an argument against curiosity, or a reminder to temper curiosity with caution? Lionni never spells out a moral in so many words, leaving that up to us.

In another tale of friendship, a fish and a tadpole reckon with the latter’s transformation into a frog. When the now-grown frog describes all he has seen above the surface of the water, the fish’s imagination conjures up very piscine versions of birds, cows, and people. Lionni’s depictions of these fish-centric creatures are clever and amusing, and introduce a problem: the fish wants to see these sights, too! His attempt to do so leaves him “gasping for air” on the bank. The frog, who happened to be nearby, pushes him back into the pond and saves his life. Are the book’s final words “fish is fish” an argument against curiosity, or a reminder to temper curiosity with caution? Lionni never spells out a moral in so many words, leaving that up to us.

David Litchfield, The Bear and the Piano (2015)

If a piano falls in the woods, does it make a sound? As this book’s title character discovers, yes it does. He learns to play, attracting, first, ursine fans, and second, a boy and a girl. The two children invite him to the city (New York), where the bear “played sold-out concerts in giant theatres.” But… he misses his home and his friends in the forest. Did they also miss him? He returns to find out. Though Litchfield (like many artists) draws upon digital tools as well as traditional artistic material, the art looks hand-made – echoes of Mary Blair, and classic Little Golden Books.

If a piano falls in the woods, does it make a sound? As this book’s title character discovers, yes it does. He learns to play, attracting, first, ursine fans, and second, a boy and a girl. The two children invite him to the city (New York), where the bear “played sold-out concerts in giant theatres.” But… he misses his home and his friends in the forest. Did they also miss him? He returns to find out. Though Litchfield (like many artists) draws upon digital tools as well as traditional artistic material, the art looks hand-made – echoes of Mary Blair, and classic Little Golden Books.

Arnold Lobel, Frog and Toad Are Friends (1970)

Inaugurating Lobel’s best-known series, Frog and Toad Are Friends introduces the key elements that make a Frog and Toad tale work. First, our two main characters are complimentary opposites: Frog is more “adult,” patient, knowledgeable, grounded. Toad tends to be more childlike, impulsive, naïve, anxious. Frog is the optimist, while Toad is more pessimistic. Frog is the go-getter, and Toad is less energetic. Second, the action revolves around a single event. In this book’s first story, Frog wants to celebrate spring, but Toad wants to keep hibernating. In the fourth story, Frog is happy to jump in the river and swim, but Toad is self-conscious about how he looks in his bathing suit. Third, they’re fables – animal characters satirize human foibles, offering a moral at the end.

Inaugurating Lobel’s best-known series, Frog and Toad Are Friends introduces the key elements that make a Frog and Toad tale work. First, our two main characters are complimentary opposites: Frog is more “adult,” patient, knowledgeable, grounded. Toad tends to be more childlike, impulsive, naïve, anxious. Frog is the optimist, while Toad is more pessimistic. Frog is the go-getter, and Toad is less energetic. Second, the action revolves around a single event. In this book’s first story, Frog wants to celebrate spring, but Toad wants to keep hibernating. In the fourth story, Frog is happy to jump in the river and swim, but Toad is self-conscious about how he looks in his bathing suit. Third, they’re fables – animal characters satirize human foibles, offering a moral at the end.  Fourth, they only imply that moral and, indeed, often subtly undercut it because, fifth, the books are funny. Lobel sees the humor in his characters and, gently, sympathetically reveals why their (especially Toad’s) choices are funny. Sixth, and most important, the two are friends. At a very basic level, all four collections of Frog and Toad stories are about friendship.

Fourth, they only imply that moral and, indeed, often subtly undercut it because, fifth, the books are funny. Lobel sees the humor in his characters and, gently, sympathetically reveals why their (especially Toad’s) choices are funny. Sixth, and most important, the two are friends. At a very basic level, all four collections of Frog and Toad stories are about friendship.

Arnold Lobel, Ranelot et Bufolet, une paire d’amis (2008) [Frog and Toad Are Friends (1970) in French]

I bought her the French edition because she’s being raised in an English-and-French-speaking household.

James Marshall, George and Martha Rise and Shine (1976)

I have already given Emily three other George and Martha books: George and Martha (1972), George and Martha Encore (1973), George and Martha Tons of Fun (1980). But there are seven books in all. And so,… I’ve added two more to her library – the third and the seventh! In this (the third), George fibs until Martha calls his bluff, Martha’s scientific inquiry into fleas make her itch, Martha’s desire for a picnic collides with George’s wish to sleep late, George thinks the scary movie will frighten Martha but she loves (in contrast, he’s more susceptible to fear than he thought), and Martha discovers the focus of George’s secret club. In each story, either George or Martha learns something, but the comedy softens the moral impulse. At their heart, these stories are about the friendship of two slightly absurd and very endearing hippos.

I have already given Emily three other George and Martha books: George and Martha (1972), George and Martha Encore (1973), George and Martha Tons of Fun (1980). But there are seven books in all. And so,… I’ve added two more to her library – the third and the seventh! In this (the third), George fibs until Martha calls his bluff, Martha’s scientific inquiry into fleas make her itch, Martha’s desire for a picnic collides with George’s wish to sleep late, George thinks the scary movie will frighten Martha but she loves (in contrast, he’s more susceptible to fear than he thought), and Martha discovers the focus of George’s secret club. In each story, either George or Martha learns something, but the comedy softens the moral impulse. At their heart, these stories are about the friendship of two slightly absurd and very endearing hippos.

James Marshall, George and Martha Round and Round (1988)

Marshall’s comic timing is as masterful as it is understated. My favorite story in this, his final George and Martha volume, is “The Last Story: The Surprise.” You think it’s over. But it ain’t over until it’s over, and Marshall gets in one final joke. These books are required in any children’s library. As Maurice Sendak says in his introduction to George and Martha: The Complete Stories of Two Best Friends, “The George and Martha books teach us nothing and everything. That is Marshall’s way. Just when you are lulled by the ease of it all, he pokes you sharply.” And, Marshall’s “simplicity is deceiving; there is richness of design and mastery of composition on every page.”

Marshall’s comic timing is as masterful as it is understated. My favorite story in this, his final George and Martha volume, is “The Last Story: The Surprise.” You think it’s over. But it ain’t over until it’s over, and Marshall gets in one final joke. These books are required in any children’s library. As Maurice Sendak says in his introduction to George and Martha: The Complete Stories of Two Best Friends, “The George and Martha books teach us nothing and everything. That is Marshall’s way. Just when you are lulled by the ease of it all, he pokes you sharply.” And, Marshall’s “simplicity is deceiving; there is richness of design and mastery of composition on every page.”

Robert Munsch and Michael Martchenko, The Paper Bag Princess (1980)

Let me be frank (OK, now you say: “Hi, Frank!”). I chose this and Kate Beaton’s The Princess and the Pony – in part – because Emily likes princesses. I want her to read books in which the princesses can save themselves. Children’s books should introduce her to smart, active princesses, not dull-witted, passive ones. And so,… this classic feminist fairy tale joins the group. When a dragon kidnaps (or prince-naps?) Prince Ronald, Princess Elizabeth sets off to find him – wearing only a paper bag because the dragon has “burned off all her clothes with his fiery breath.” She outsmarts the dragon and rescues the prince! But Ronald turns out to be snooty and ungrateful. So – spoiler alert! – she does not marry him after all. The end.

Let me be frank (OK, now you say: “Hi, Frank!”). I chose this and Kate Beaton’s The Princess and the Pony – in part – because Emily likes princesses. I want her to read books in which the princesses can save themselves. Children’s books should introduce her to smart, active princesses, not dull-witted, passive ones. And so,… this classic feminist fairy tale joins the group. When a dragon kidnaps (or prince-naps?) Prince Ronald, Princess Elizabeth sets off to find him – wearing only a paper bag because the dragon has “burned off all her clothes with his fiery breath.” She outsmarts the dragon and rescues the prince! But Ronald turns out to be snooty and ungrateful. So – spoiler alert! – she does not marry him after all. The end.

Mark Pett, The Lizard from the Park (2015)

A charming example of incidental diversity (Leonard’s brown complexion plays no larger role in the story), Pett‘s The Lizard from the Park seems to be about a solitary boy (Leonard) who finds a lizard egg, which hatches, and soon grows into a dinosaur. However, as this narrative unfolds, some contrary clues emerge. When they are out in public, no one notices Leonard’s increasingly large lizard. Indeed, the only person who seems to notice either Leonard or Buster (his lizard) is a bespectacled boy who – though never mentioned in the text – keeps crossing paths with Leonard in the illustrations. But it’s not clear whether this boy is noticing Leonard or his lizard or both… until the book’s conclusion, which I won’t give away here.

A charming example of incidental diversity (Leonard’s brown complexion plays no larger role in the story), Pett‘s The Lizard from the Park seems to be about a solitary boy (Leonard) who finds a lizard egg, which hatches, and soon grows into a dinosaur. However, as this narrative unfolds, some contrary clues emerge. When they are out in public, no one notices Leonard’s increasingly large lizard. Indeed, the only person who seems to notice either Leonard or Buster (his lizard) is a bespectacled boy who – though never mentioned in the text – keeps crossing paths with Leonard in the illustrations. But it’s not clear whether this boy is noticing Leonard or his lizard or both… until the book’s conclusion, which I won’t give away here.

Sergio Ruzzier, This Is Not a Picture Book (2016)

Ruzzier has created a clever, engaging book about learning to read – which, as you might expect, 5-year-old Emily will soon be doing. The narrative starts on the partially decipherable initial endpapers, which garbles most words but leaves some legible. Though we may not at first realize it, the pages subtly convey the partial comprehension of a beginning reader. Then, against a completely white background, a duckling finds a book, picks it up, opens it, notes that it has no pictures, and speaks the title (as the title, on the title page). As soon as the friendly bug prompts duckling to start reading, the blank landscape acquires color and sprouts visual metaphors for the duckling’s recognition of certain words. For the page indicating “funny” words, smiling bubbles drift by, a long-nosed large-footed fellow naps near a flowerpot, and many whimsical creatures look on. For “sad,” duckling and bug walk past smoldering houses and the craters of a recently bombed landscape. By the book’s conclusion, the duckling can read – and the final endpapers have transformed into a legible typographic rendition of This Is Not a Picture Book!’s plot. Without any whiff of didacticism, the visual intelligence of Ruzzier’s book makes a subtle case for the pleasures of literacy.

Ruzzier has created a clever, engaging book about learning to read – which, as you might expect, 5-year-old Emily will soon be doing. The narrative starts on the partially decipherable initial endpapers, which garbles most words but leaves some legible. Though we may not at first realize it, the pages subtly convey the partial comprehension of a beginning reader. Then, against a completely white background, a duckling finds a book, picks it up, opens it, notes that it has no pictures, and speaks the title (as the title, on the title page). As soon as the friendly bug prompts duckling to start reading, the blank landscape acquires color and sprouts visual metaphors for the duckling’s recognition of certain words. For the page indicating “funny” words, smiling bubbles drift by, a long-nosed large-footed fellow naps near a flowerpot, and many whimsical creatures look on. For “sad,” duckling and bug walk past smoldering houses and the craters of a recently bombed landscape. By the book’s conclusion, the duckling can read – and the final endpapers have transformed into a legible typographic rendition of This Is Not a Picture Book!’s plot. Without any whiff of didacticism, the visual intelligence of Ruzzier’s book makes a subtle case for the pleasures of literacy.

Julia Sacrone-Roach, The Bear Ate Your Sandwich (2015)

“By now I think you may know what happened to your sandwich,” the unseen narrator advises us. “But you may not know how it happened. So let me tell you. It all started with the bear.” So begins Sarcone-Roach’s very funny story of how a bear just happened to arrive in the city, and the park, and eat your sandwich. Though the tale is framed as an excuse, by concealing both the narrator and any evidence of sandwich-thievery, Sarcone-Roach invites us to be swept up into the improbable narrative. Her bright paint-and-pencil illustrations bring us along on the bear’s journey to, and then new experiences in the city. Only at the very end does she reveal that the whole story has been an elaborate set-up for the punchline – which, no, I won’t reveal here.

“By now I think you may know what happened to your sandwich,” the unseen narrator advises us. “But you may not know how it happened. So let me tell you. It all started with the bear.” So begins Sarcone-Roach’s very funny story of how a bear just happened to arrive in the city, and the park, and eat your sandwich. Though the tale is framed as an excuse, by concealing both the narrator and any evidence of sandwich-thievery, Sarcone-Roach invites us to be swept up into the improbable narrative. Her bright paint-and-pencil illustrations bring us along on the bear’s journey to, and then new experiences in the city. Only at the very end does she reveal that the whole story has been an elaborate set-up for the punchline – which, no, I won’t reveal here.

Francesca Sanna, The Journey (2016)

This is one of my favorite picture books of 2016. It’s timely, yes, but its strength lies in Sanna’s deft visual storytelling – her sense of pacing, design, story. It’s very well done. As war arrives, a family loses its father, and must seek a safe harbor. On the page where “The war began,” the darkness that (on the previous two-page spread) had represented the sea suddenly becomes menacing, overtaking the entire right-hand page, with giant shadowy hands reaching left, destroying buildings. Over a few subsequent two-page spreads, the gradual loss of the family’s baggage accrues the weight of a much deeper loss – of home, father, security. With relatively spare text and powerful, vivid art, the book takes us on their journey toward what they hope will be their new home. Wisely, The Journey ends before the journey is complete. Narrated from the perspective of one of the two children in the family, the book delivers a complex, emotionally layered story with economy and subtlety. It neither sugarcoats its serious subject, nor presents in a too emotionally charged manner. It’s a book you’ll return to.

This is one of my favorite picture books of 2016. It’s timely, yes, but its strength lies in Sanna’s deft visual storytelling – her sense of pacing, design, story. It’s very well done. As war arrives, a family loses its father, and must seek a safe harbor. On the page where “The war began,” the darkness that (on the previous two-page spread) had represented the sea suddenly becomes menacing, overtaking the entire right-hand page, with giant shadowy hands reaching left, destroying buildings. Over a few subsequent two-page spreads, the gradual loss of the family’s baggage accrues the weight of a much deeper loss – of home, father, security. With relatively spare text and powerful, vivid art, the book takes us on their journey toward what they hope will be their new home. Wisely, The Journey ends before the journey is complete. Narrated from the perspective of one of the two children in the family, the book delivers a complex, emotionally layered story with economy and subtlety. It neither sugarcoats its serious subject, nor presents in a too emotionally charged manner. It’s a book you’ll return to.

Lemony Snicket & Jon Klassen, The Dark (2013)

I bought this one because I noticed that Emily – at age 4, at least – needed a night-light. So, I thought: perhaps it would be helpful for her to read a story about making friends with the dark. That is precisely what The Dark is about. At the book’s beginning, Laszlo is afraid of the dark. Snicket and Klassen set up the dark as a character: “The dark lived in the same house as Laszlo,” they tell us on an early two-page spread. When Laszlo greets the dark, it (the dark) is silent. Then, one day, it addresses him directly, luring him down to the basement, where it lives. The story invokes this horror-story trope so that it can bring us into darkness while it demystifies darkness. I won’t give away the ending, but – as you may have guessed – by book’s conclusion, Laszlo no longer fears the dark.

I bought this one because I noticed that Emily – at age 4, at least – needed a night-light. So, I thought: perhaps it would be helpful for her to read a story about making friends with the dark. That is precisely what The Dark is about. At the book’s beginning, Laszlo is afraid of the dark. Snicket and Klassen set up the dark as a character: “The dark lived in the same house as Laszlo,” they tell us on an early two-page spread. When Laszlo greets the dark, it (the dark) is silent. Then, one day, it addresses him directly, luring him down to the basement, where it lives. The story invokes this horror-story trope so that it can bring us into darkness while it demystifies darkness. I won’t give away the ending, but – as you may have guessed – by book’s conclusion, Laszlo no longer fears the dark.

Helen Stephens, How to Hide a Lion (2012)

A book that feels like it could have been published decades ago – in the 1960s, or maybe 1930s. With a line that recalls Edward Ardizozne and watercolors that recall Marcia Brown, Helen Stephens tells of a lion who strolled into a market square to buy a hat, but frightened townspeople chase him out of town… and so he meets Iris, a brave small girl who befriends him and helps him hide. I haven’t seen this in the U.S., but it’s been popular enough in the U.K. (where I found it) to inspire a sequel, How to Hide a Lion from Grandma. (I haven’t read the sequel.)

A book that feels like it could have been published decades ago – in the 1960s, or maybe 1930s. With a line that recalls Edward Ardizozne and watercolors that recall Marcia Brown, Helen Stephens tells of a lion who strolled into a market square to buy a hat, but frightened townspeople chase him out of town… and so he meets Iris, a brave small girl who befriends him and helps him hide. I haven’t seen this in the U.S., but it’s been popular enough in the U.K. (where I found it) to inspire a sequel, How to Hide a Lion from Grandma. (I haven’t read the sequel.)

Koen Van Biesen, Roger Is Reading a Book (2015; orig. published as Buurman leest een boek, 2012)

Roger is reading a book. Or he is trying to. Next door, Emily is playing with a ball (BOING BOING). Roger asks her to please Shhhh! This pattern of different noises followed by Shhhh! repeats – until Roger puts down his book, and leaves. Then, a package arrives for Emily. It’s a book! Roger returns, and both read in silence . . . until WOOF WOOF WOOF WOOF WOOF. They both put down their books and take the dog – whom Roger has been ignoring for several two-page spreads – for a walk. In addition to the book’s spare illustration (not finishing the top of Roger’s head, for instance), I like how it takes both Roger and Emily seriously. Neither intends to be obnoxious to the other. Their interests differ. The character’s names also assert their independence. Never does Koen Van Biesen indicate their relationship to one another. Roger is not identified as Emily’s father or uncle or caregiver. He is just Roger. She might live in the apartment next to his, or might live in the same apartment. Her bedroom is adjacent to the room where he’s trying to read, and he always knocks before he enters. But that’s all we know. Also, yes, one of the main characters is Emily – which I thought would please the real Emily.

Roger is reading a book. Or he is trying to. Next door, Emily is playing with a ball (BOING BOING). Roger asks her to please Shhhh! This pattern of different noises followed by Shhhh! repeats – until Roger puts down his book, and leaves. Then, a package arrives for Emily. It’s a book! Roger returns, and both read in silence . . . until WOOF WOOF WOOF WOOF WOOF. They both put down their books and take the dog – whom Roger has been ignoring for several two-page spreads – for a walk. In addition to the book’s spare illustration (not finishing the top of Roger’s head, for instance), I like how it takes both Roger and Emily seriously. Neither intends to be obnoxious to the other. Their interests differ. The character’s names also assert their independence. Never does Koen Van Biesen indicate their relationship to one another. Roger is not identified as Emily’s father or uncle or caregiver. He is just Roger. She might live in the apartment next to his, or might live in the same apartment. Her bedroom is adjacent to the room where he’s trying to read, and he always knocks before he enters. But that’s all we know. Also, yes, one of the main characters is Emily – which I thought would please the real Emily.

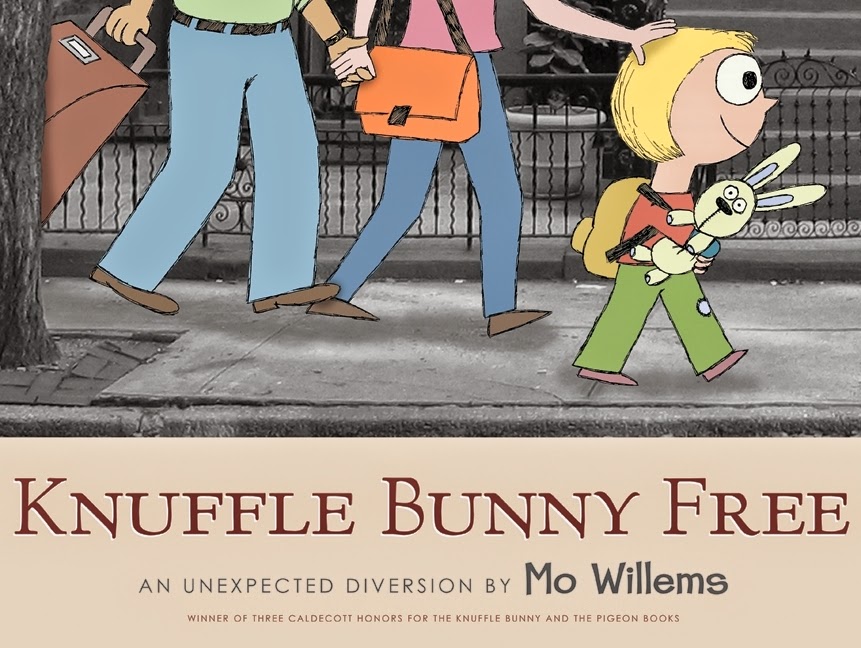

Mo Willems, Knuffle Bunny Free (2010)

The conclusion to Willems’ trilogy featuring Trixie, her bunny, and Trixie’s parents. (Emily already has the first two: Knuffle Bunny [2004] and Knufffle Bunny [2007].) Using the now familiar combination of black-and-white photos (for the setting) with hand-inked drawings (for the people and select objects), Willems brings Trixie and her parents to the Netherlands to see Oma and Opa (Grandma and Grandpa). Guess what she leaves on the plane? Now older, Trixie learns to live without her knuffle bunny and even to consider that, perhaps, other, younger children may need him more than she does. If a bit more sentimental than the previous two books, Willems’ tale and its morals nonetheless arrive via the sharply observed humor that makes a Mo Willems book a Mo Willems book.

The conclusion to Willems’ trilogy featuring Trixie, her bunny, and Trixie’s parents. (Emily already has the first two: Knuffle Bunny [2004] and Knufffle Bunny [2007].) Using the now familiar combination of black-and-white photos (for the setting) with hand-inked drawings (for the people and select objects), Willems brings Trixie and her parents to the Netherlands to see Oma and Opa (Grandma and Grandpa). Guess what she leaves on the plane? Now older, Trixie learns to live without her knuffle bunny and even to consider that, perhaps, other, younger children may need him more than she does. If a bit more sentimental than the previous two books, Willems’ tale and its morals nonetheless arrive via the sharply observed humor that makes a Mo Willems book a Mo Willems book.

Looking for other great children’s books? Try these blogs and other websites:

- Elizabeth Bird’s Fuse #8

- Julie Walker Danielson’s Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast – a major source for the new picture books, above.

- Travis Jonker’s 100 Scope Notes

- Anita Silvey’s Children’s Book-a-Day Almanac

- Follow The Niblings on Twitter or Facebook

- Teaching for Change‘s Favorite Books of 2015

- We Need Diverse Books‘ Resources on Where to Find Diverse Books

Related posts on Nine Kinds of Pie:

- Emily’s Library, Part 1: 62 Great Books for the Very Young (2 Jan. 2012)

- Emily’s Library, Part 2: Wordless Picture Books (3 Jan. 2012)

- Emily’s Library, Part 3: En Français (4 Jan. 2012)

- Emily’s Library, Part 4: Ten Alphabet Books (24 Feb. 2012)

- Emily’s Library, Part 5: 29 More Books for the Very Young (22 May 2012)

- Emily’s Library, Part 6: 35 More Books for the Very Young (21 April 2013)

- Emily’s Library, Part 7: 31 Good Books for Small Humans (19 Jan. 2014)

- Emily’s Library, Part 8: 25 Fine Books for Small People; or, Further Adventures in Building the Ideal Children’s Library (12 Dec. 2014)

- Emily’s Library, Part 9: 14 More Books for Young Reaers (29 July 2015)

- How to Find Good Children’s Books (April 2011)

- Desert Island Picture Books (Oct. 2011)

- Mock Caldecott, 2016: Manhattan, Kansas Edition (Dec. 2016)

- Mock Caldecott, 2014: Manhattan, Kansas Edition (Dec. 2014)

- Mock Caldecott, 2013: Manhattan, Kansas Edition (Dec. 2013)

- Mock Caldecott, 2012: Manhattan, Kansas Edition (Dec. 2012)

- Mock Caldecott, 2011: Manhattan, Kansas Edition (Dec. 2011)

- Mock Caldecott, 2010: Manhattan, Kansas Edition (Dec. 2010)

Jonathan

Philip Nel