The objects of your nostalgic longing may disappoint you, if you are willing to look at them openly and honestly. If you read, create, or write about children’s literature, today – the 114th birthday of Theodor Geisel (a.k.a. Dr. Seuss) – would be a good time to admit this to yourself. OK, the time for such admission is really long overdue, but do not be too hard on yourself. The power of cultural inertia is hard to resist.

That said, do resist. Make the attempt. As Seuss himself wrote in a different context, “face up to your problems / whatever they are.”

This particular problem is one to tackle today because Seuss’s work contains both much to admire and much to oppose. Yet, because of his status, people are much more comfortable admiring than looking critically at his work. In the U.S., he is revered as a patron saint of children’s literacy, and children’s literature. In 1997, the National Education Association adopted his birthday as a day to celebrate “Read Across America Day.” It still uses his Cat in the Hat as its mascot, even though – starting this year – it’s shifting its focus to diverse books.

This particular problem is one to tackle today because Seuss’s work contains both much to admire and much to oppose. Yet, because of his status, people are much more comfortable admiring than looking critically at his work. In the U.S., he is revered as a patron saint of children’s literacy, and children’s literature. In 1997, the National Education Association adopted his birthday as a day to celebrate “Read Across America Day.” It still uses his Cat in the Hat as its mascot, even though – starting this year – it’s shifting its focus to diverse books.

I am partly to blame for this shift.

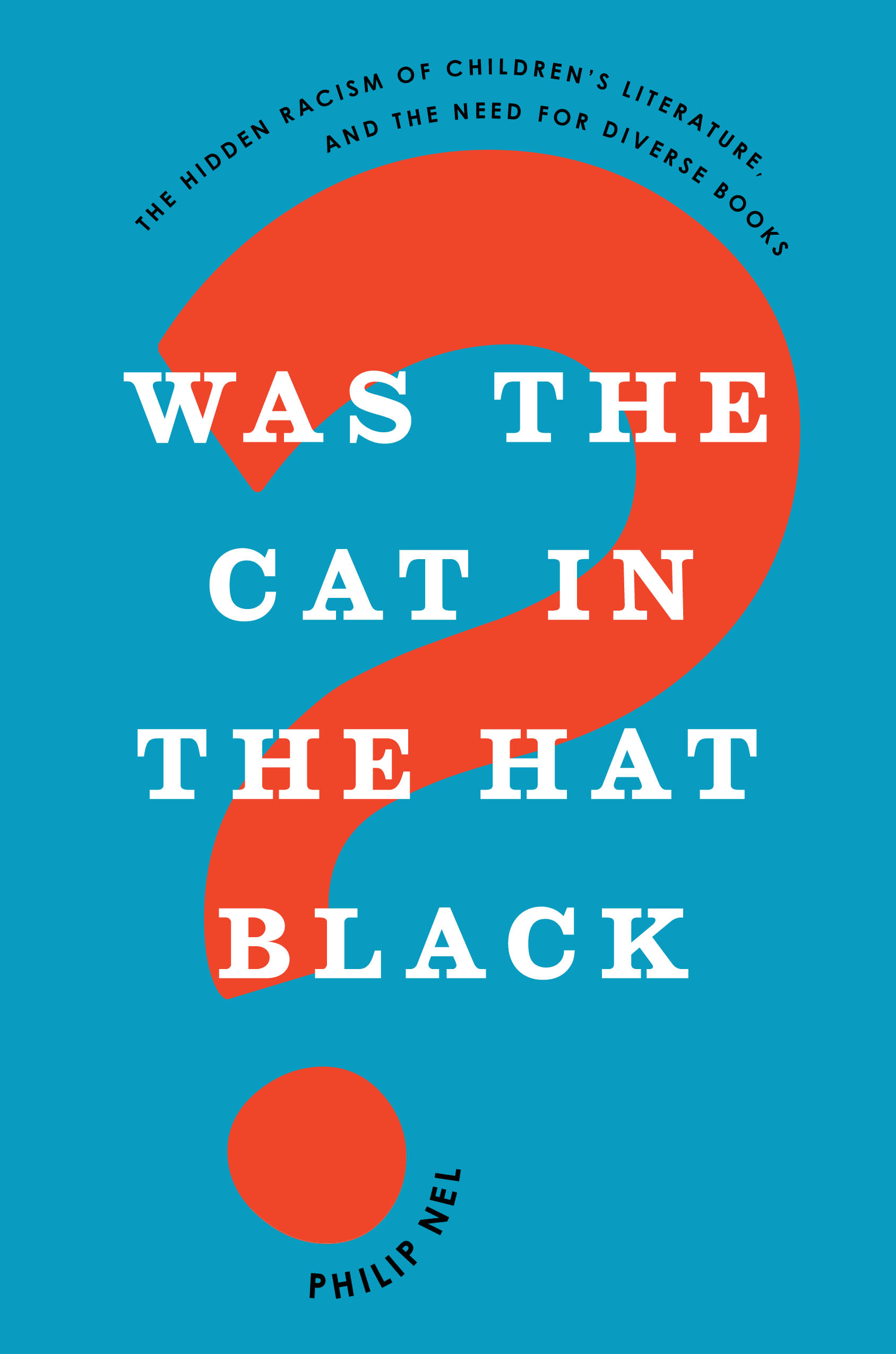

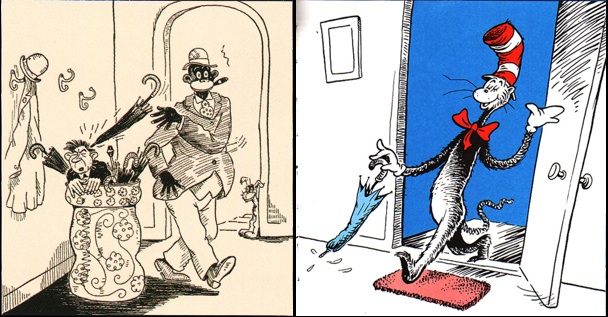

In a report that helped inspire this change, Katie Ishizuka-Stephens cites the essay that became the title chapter of my Was the Cat in the Hat Black? As I point out, Seuss’s Cat is racially complicated. He’s partially inspired by blackface minstrelsy, African American elevator operator Annie Williams (who wore white gloves and a secret smile), and Krazy Kat (the black, ambiguously gendered creation of bi-racial cartoonist George Herriman).

In a report that helped inspire this change, Katie Ishizuka-Stephens cites the essay that became the title chapter of my Was the Cat in the Hat Black? As I point out, Seuss’s Cat is racially complicated. He’s partially inspired by blackface minstrelsy, African American elevator operator Annie Williams (who wore white gloves and a secret smile), and Krazy Kat (the black, ambiguously gendered creation of bi-racial cartoonist George Herriman).

I’m happy that Ishizuka-Stephens’s report has persuaded the NEA to shift their “Read Across America Day” focus to diverse books. Half of U.S. school-age children are nonwhite. But of children’s books published in 2016, only 22 percent of children’s books published featured nonwhite children, and only 13 percent were by nonwhite creators. Celebrating stories in which our multicultural young people can see themselves is a better choice than celebrating Seuss.

Which is not to say that Seuss must be thrown out of our classrooms – though that is of course an option. It is, rather, to suggest that we consider which Seuss we use, and how we use it.

At left: Dr. Seuss, from “Four Places Not to Hide While Growing Your Beard” (Life, 15 Nov. 1929). At right: Dr. Seuss, The Cat in the Hat (1957).

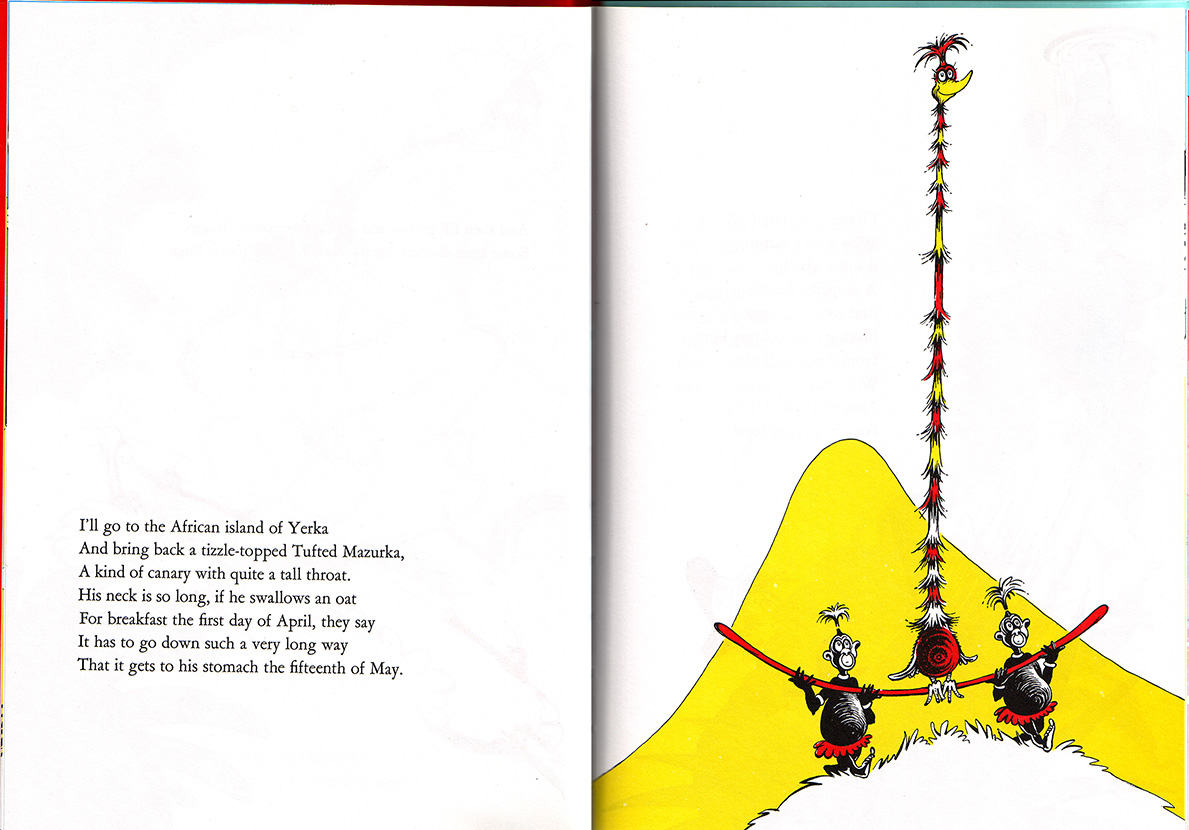

Racial caricature in Seuss’s work can help people understand how racism works. Seuss did both racist work and anti-racist work, often at the same time. In the 1940s, he created political cartoons, some of which dehumanized people of Japanese descent, and others of which were critical of both anti-Semitism and racism against African Americans. In the 1950s, Seuss published Horton Hears a Who!, hailed by one reviewer as “a rhymed lesson in protection of minorities and their rights”; wrote his first version of The Sneetches, an anti-racist fable; and published an essay that critiques racist humor. During that same period, he recycled racist caricature in his books. In If I Ran the Zoo, protagonist Gerald McGrew travels to “the mountains of Zomba-ma-Tant / With helpers who all wear their eyes at a slant,” and to the “African Island of Yerka” where he meets two stereotypically rendered Black men.

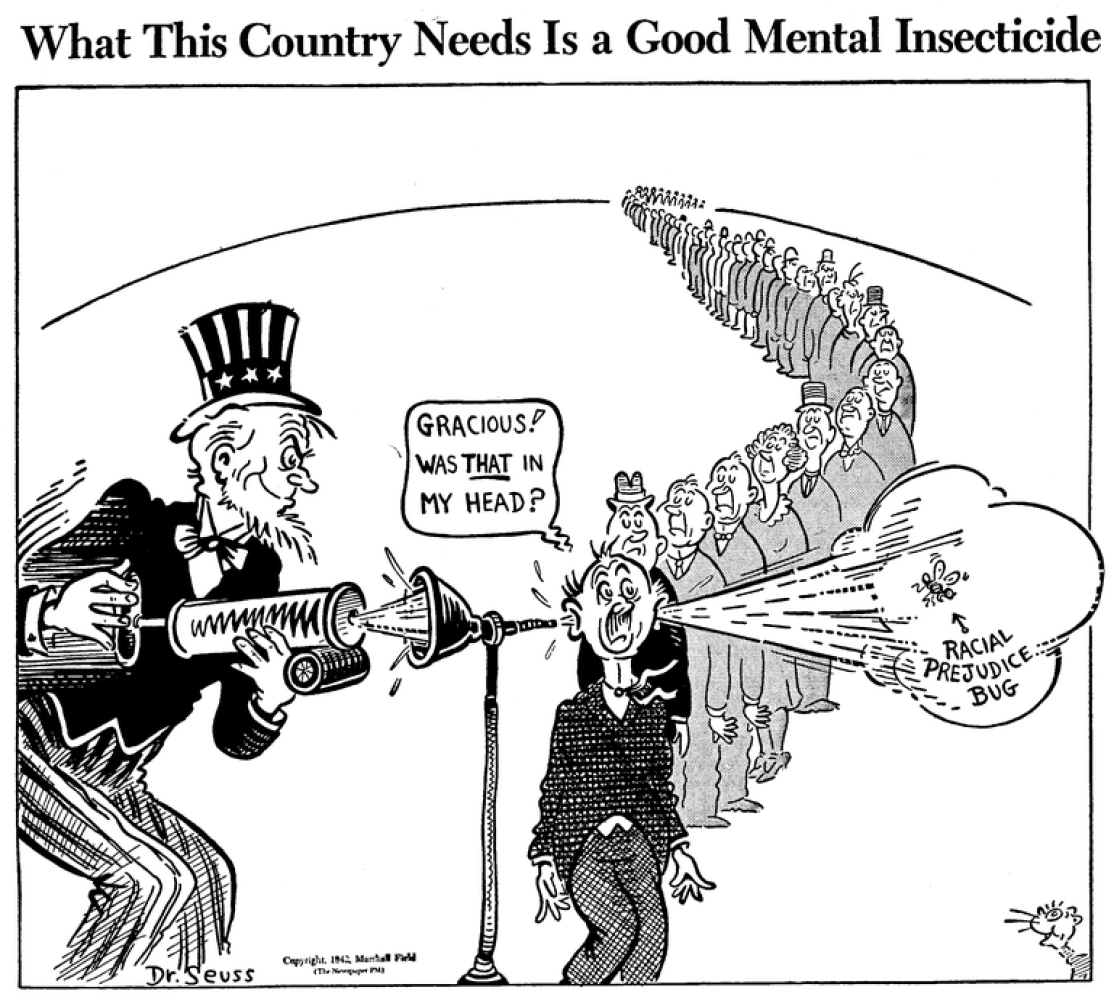

That Seuss is doing both racist anti-racist work at the same time can be confusing because many of us see racism as an “either/or”: people are either racist or not racist. Indeed, that’s how Seuss himself understood racism. In a June 1942 cartoon titled “What This Country Needs is a Good Mental Insecticide,” he draws a long line of men waiting to get inoculated against the “racial prejudice bug.” The insecticide goes in one ear, and the racist bug tumbles out the other. I wish we could fumigate racism from our minds, and applaud Seuss’s optimism. Unfortunately, racism is not a bug. It’s a feature. Racism is not aberrant. It’s ordinary. It’s embedded in institutions and in culture – such as the cartoons and books of Dr. Seuss.

It’s upsetting to learn that a beloved children’s author used racist caricature. So, many people – especially White people – seek explanations and offer excuses. In response to recent criticism, his grand-nephew Ted Owens has said of Seuss: “I know one thing for sure – I never saw one ounce of racism in anything he said, or how he lived his life, or what his stories were about.” Mr. Owens’ claim relies on perception and intent. But racism does not require either. People can perpetuate racism without intending to. I don’t think Seuss intended to. Because he was unaware of the degree to which his visual imagination was steeped in caricature, he recycled racist stereotypes even as he was also writing anti-racist parables. Dr. Seuss was the “woke” White guy who isn’t as woke as he thinks he is.

“Now, wait just a minute,” some may object. “Seuss was a man of his time. We should not impose contemporary standards on him or his work. People thought differently then.” But that is a gross oversimplification. All people in any given historical moment do not think about race in precisely the same way. As Robin Bernstein has shown in her work on nineteenth-century anti-racism, the range of available racial beliefs remains constant over time, but the distribution of those beliefs change. In the past and in the present, both extraordinary and perfectly ordinary people have opposed White supremacy. Similarly, both remarkable and unremarkable people have supported White supremacy. To claim that people 60 years ago were racist but people now are enlightened both naturalizes past racism as inevitable and implies that social change is a natural, ongoing march towards a brighter, fairer future. Yet, as we are reminded daily, our current president and his party are actively working against precisely such a future. Progress moves in fits and starts, makes gains and endures setbacks, and always requires people committed to making a positive difference.

“Now, wait just a minute,” some may object. “Seuss was a man of his time. We should not impose contemporary standards on him or his work. People thought differently then.” But that is a gross oversimplification. All people in any given historical moment do not think about race in precisely the same way. As Robin Bernstein has shown in her work on nineteenth-century anti-racism, the range of available racial beliefs remains constant over time, but the distribution of those beliefs change. In the past and in the present, both extraordinary and perfectly ordinary people have opposed White supremacy. Similarly, both remarkable and unremarkable people have supported White supremacy. To claim that people 60 years ago were racist but people now are enlightened both naturalizes past racism as inevitable and implies that social change is a natural, ongoing march towards a brighter, fairer future. Yet, as we are reminded daily, our current president and his party are actively working against precisely such a future. Progress moves in fits and starts, makes gains and endures setbacks, and always requires people committed to making a positive difference.

Seuss can be part of this positive difference. His more progressive books – The Lorax (1971) or The Butter Battle Book (1984), to name two examples – might teach children about the need to care for the environment or to oppose the proliferation of nuclear weapons. Horton Hears a Who! could teach them to stand up for those who are targeted by bigots: the Whos’ size is an arbitrary mark of difference that could represent any such visible sign of human variance. As for the books featuring racist caricature, one option is to remove them from the curriculum. Another is to read them critically. With the guidance of a thoughtful educator, Seuss’s racist caricature can help young people understand that racism is not anomalous. It permeates the culture. Seeing this caricature can also let them know that it’s OK to be angry at art – that anger can in fact be a healthy response to work that demeans you.

Seuss can be part of this positive difference. His more progressive books – The Lorax (1971) or The Butter Battle Book (1984), to name two examples – might teach children about the need to care for the environment or to oppose the proliferation of nuclear weapons. Horton Hears a Who! could teach them to stand up for those who are targeted by bigots: the Whos’ size is an arbitrary mark of difference that could represent any such visible sign of human variance. As for the books featuring racist caricature, one option is to remove them from the curriculum. Another is to read them critically. With the guidance of a thoughtful educator, Seuss’s racist caricature can help young people understand that racism is not anomalous. It permeates the culture. Seeing this caricature can also let them know that it’s OK to be angry at art – that anger can in fact be a healthy response to work that demeans you.

We might also follow Roxane Gay’s advice. As she writes, “There is no scarcity of creative genius, and that is the artistic work we can and should turn to instead.” Gay is writing in the context of the current #MeToo movement, suggesting that we discard work built on the dehumanization of others. We could follow her advice by pushing Seuss aside and instead celebrating diverse books – doing what the NEA is doing in its program even if it (curiously) retains the Cat in the Hat as its mascot. Ishizuka-Stephens has assembled a great collection of “21 Books for an Inclusive Read Across America Day.” That’s an excellent place to start.

Wrapping yourself in an unreflective nostalgia for the art you grew up with may comfort you, but if that art denigrates women, or caricatures people of color, or otherwise harms minoritized communities, then you bear responsibility for the pain that this art inflicts. I realize this is a hard truth to face and that some who read this will – instead of facing themselves and acknowledging their responsibility – attack the messenger. Some may indulge in projection, locating in the messenger those faults that they refuse to admit in themselves. Others will find different strategies of denial, displacement, or dismissal. In so doing, they will continue to be part of the problem.

For those who prefer to be part of the solution, know that you need not abandon nostalgia. It’s OK to be nostalgic, as long as that nostalgia is what Svetlana Boym called “reflective nostalgia.” It “dwells on the ambivalences of human longing and belonging and does not shy away from the contradictions of modernity. Restorative nostalgia protects the absolute truth, while reflective nostalgia calls it into doubt” (xviii). As Boym wrote, reflective nostalgia reminds us that “longing and critical thinking are not opposed to one another, as affective memories do not absolve one from compassion, judgment or critical reflection” (The Future of Nostalgia 49-50).

For those who prefer to be part of the solution, know that you need not abandon nostalgia. It’s OK to be nostalgic, as long as that nostalgia is what Svetlana Boym called “reflective nostalgia.” It “dwells on the ambivalences of human longing and belonging and does not shy away from the contradictions of modernity. Restorative nostalgia protects the absolute truth, while reflective nostalgia calls it into doubt” (xviii). As Boym wrote, reflective nostalgia reminds us that “longing and critical thinking are not opposed to one another, as affective memories do not absolve one from compassion, judgment or critical reflection” (The Future of Nostalgia 49-50).

So. Reflect. Dwell on those ambivalences. Develop your capacity to reflect. Activate your compassion.

And buy diverse books. Teach diverse books. Read diverse books.

Posts related to Was the Cat in the Hat Black?, including glimpses of the work in progress:

- Was the Cat in the Hat Black? (Talks @ Google) (25 Sept. 2017)

- 7 Questions We Should Ask About Children’s Literature (19 Sept. 2017)

- Free Book: Goodreads Giveaway of Was the Cat in the Hat Black? (1 Sept. 2017)

- Racism & Seuss: It’s not a bug. It’s a feature. (A Twitter Essay) (12 Aug. 2017)

- Was the Cat in the Hat Black? – cover reveal (19 Dec. 2016).

- Was the Cat in the Hat Black?: The Hidden Racism of Children’s Literature, and Why We Need Diverse Books (4 Dec. 2015). The announcement of the book’s publication. It inspired a response from Debbie Reese, which in turn prompted me to change the title. Upon learning that “We Need Diverse Books” is trademarked (by the excellent We Need Diverse Books organization), I changed “Why We Need Diverse Books” to “the Need for Diverse Books.”

- The Archive of Childhood, Part 2: The Golliwog (13 Jan. 2015). A revised version of this blog post appears as part of the book’s introduction (“Race, Racism, and the Cultures of Childhood”).

- Was the Cat in the Hat Black? (22 June 2014). An earlier version of the title chapter (“The Strange Career of the Cat in the Hat; or, Dr. Seuss’s Racial Imagination”) appeared as an article, in Children’s Literature 42 (2014).

- On Reading the Expurgated Huck Finn; or, Why We Should Teach Offensive Novels (17 Oct. 2014). I wrote this blog post so that I could write about Alan Gribben’s expurgated edition of Twain. Pieces of this appear (in revised form) in Chapter 2, “How to Read Uncomfortably: Racism, Affect, and Classic Children’s Books.”

- Can Censoring a Children’s Book Remove Its Prejudices? (19 Sept. 2010). My earliest thinking on what became Chapter 2 (“How to Read Uncomfortably”), and one of the most frequently cited posts from this blog. I hope that – in future – people cite the book chapter… because it’s better!

- “The Boundaries of Imagination”; or, the All-White World of Children’s Books, 2014 (17 March 2014). On the occasion of the New York Times pieces by Christopher Myers and Walter Dean Myers, a collection of information and essays about the fight for diversity in children’s literature.

- Disagreement, Difference, Diversity: A Talk by Christopher Myers (24 Oct. 2015). A few thoughts and notes on an excellent talk by Christopher Myers. I quote from his talk in the book.

- Regarding the Pain of Racism (4 Apr. 2015). Reflections on an observation by Naomi Murakawa, and on my challenges as a White male scholar writing about oppressions I have not experienced. A few slivers of this appear in the Conclusion, “A Manifesto for Anti-Racist Children’s Literature.”

- Ferguson: Response & Resources (24 Aug. 2014). I began this book before the Black Lives Matter movement began, but it and its leaders have informed my work.

- #BlackLivesMatter – A Twitter Essay (3 Dec. 2014). Daniel Pantaleo is on video choking Eric Garner to death. When a grand jury said there was no need for a trial, I wrote this.

- Again. And Again. And… ENOUGH! (7 July 2016). The murders of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile inspired this. #BlackLivesMatter

- Charleston, Family History, and White Responsibility (22 June 2016). A response to the terrorism in Charleston, South Carolina. Following sustained critique from family members, I removed this from the blog – the first time that I’ve altered a post for reasons other than finding an error or a typo. However, the Wayback Machine preserved the post. Ideas expressed in it emerge in the book (notably, the end of Chapter 3), but (unlike the original post) do so without identifying specific individuals.

Some previous posts on Seuss

- Seuss’s Matilda: Horton’s Ancestor (2 Mar. 2017)

- How Do We Stop the Trump on the Stump? The Truth Is in Seuss! (28 March 2016). From my ears to the American electorate. (Results of the warning were, um, mixed. At best.)

- Seuss on Film (2 March 2016). Includes four clips of Seuss: Unusual Occupations (1940), Making SNAFU (c. 1943), To Tell the Truth (1958), and footage from a New Zealand schoolroom (1964).

- No Seuss Better Than Faux Seuss (27 July 2015). On bad imitation Seuss verse, contrasted with good imitation – provided via audio of David Rakoff’s excellent “Samsa and Seuss.”

- Six Spots of Seuss News (2 Mar. 2015). On What Pet Should I Get?, Elana Kagan’s citation of One fish two fish red fish blue fish (1960) in a 2015 Supreme Court decision written by Justice Elena Kagan, Dr. Seuss advertising art from 1936, and a Dr. Seuss rap quiz!

- Oh, the Quotations You’ll Forge! (2 Mar. 2014). Seuss’s pithy verse is very quotable. Unfortunately, people have a habit of attributing things to him that he never said. This post exposes some fake Seuss, and gives you plenty of quotations that he actually did say.

- Happy birthday to Dr. Seuss! A guest post by Charles D. Cohen (2 Mar. 2013). Birthday reflections from Seussologist Charles Cohen (The Seuss, the Whole Seuss, and Nothing But the Seuss). Quotes some original verse by Seuss, including “Pentellic Bilge for Bennett Cerf’s Birthday” (1940).

- How to Mispronounce “Dr. Seuss” (6 Feb. 2013). Also: how to pronounce “Dr. Seuss.”

- I Am the Lorax. I Speak for the Theeds? (3 Mar. 2012). Some thoughts on The Lorax film and its attendant advertising.

- Dr. Seuss: children’s books “have a greater potential for good or evil, than any other form of literature on earth.” (1 Mar. 2012). A 1960 essay by Seuss on writing for children.

- Dr. Seuss on “conditioned laughter,” racist humor, and why adults are “obsolete children” (16 Jan. 2012). A 1952 essay by Seuss on humor.

- Seussology (15 Jan. 2012): On my graduate-level “Dr. Seuss” course.

- Oh, the Thinks That He Thought! Some of Seuss’s Lesser-Known Works (2 Mar. 2011): My post for Dr. Seuss’s birthday in 2011.

- You’re a Mean One, Mr. Grinch (20 Dec. 2010): 15 versions of the song.

- Corporate Seuss; or, Oh, the Things You Can Sell! (21 Aug. 2010). Ted Geisel was first famous for advertising, not children’s books.

Public Librarian

Philip Nel

Public Librarian

Philip Nel

Pingback: Why schools should rethink Dr. Seuss - Book Publishing

Pingback: Is It Time to Move On From Dr. Seuss? - Inspiration, Creativity, Wonder.

Pingback: Is It Time to Move On From Dr. Seuss? – THE FLENSBURG FILES